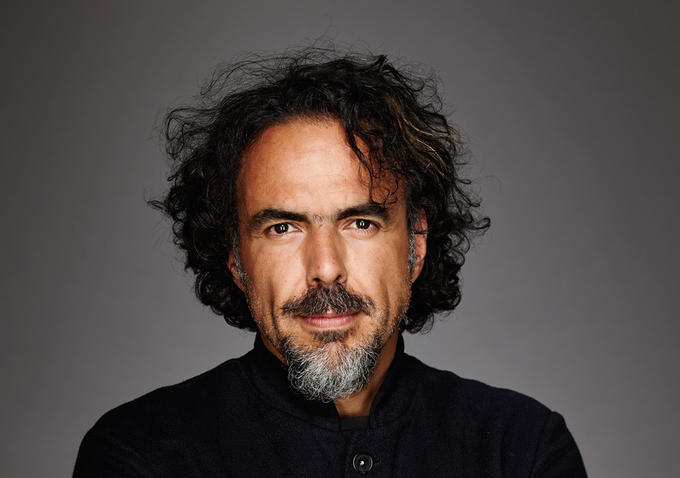

“Everybody is looking for validation, no matter who you are, and I think that’s a need of the human condition-to look for affection or recognition or validation” – Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu

Inarritu is one of the finest artist of our generation. He may lack Spielberg’s versatility as every film of his are deeply rooted in humanistic relations and values. But he is master of his craft, none of the present filmmakers comprehend human conditions better than Inarritu. From traversing interconnected human relations on the streets of Mexico to encompass human emotions virtually anywhere in the planet. He made us aware that even though we are different from each other in terms of culture, language and traditions, there is a sense of underlying commonality we all share. In a world defined by politics, greed, power and authoritarian regimes, he made us realize that comprehending human connectedness may be essential for the ethical future of the planet. This underlying notion of codependency was pervasive in his much famed “Death Trilogy” ( Amores Perros, 21 grams, Babel) . He narrates multiple stores pivoting around an existential moment in all three films. In these three films, he allowed individual to take the center stage and put them in situations which tests their morality, principles, decisions and ethics. Human frailty, resilience, and validation were fundamental themes explored in these films. Now let’s scrutinize each of his films with much more clarity.

Inarritu is one of the finest artist of our generation. He may lack Spielberg’s versatility as every film of his are deeply rooted in humanistic relations and values. But he is master of his craft, none of the present filmmakers comprehend human conditions better than Inarritu. From traversing interconnected human relations on the streets of Mexico to encompass human emotions virtually anywhere in the planet. He made us aware that even though we are different from each other in terms of culture, language and traditions, there is a sense of underlying commonality we all share. In a world defined by politics, greed, power and authoritarian regimes, he made us realize that comprehending human connectedness may be essential for the ethical future of the planet. This underlying notion of codependency was pervasive in his much famed “Death Trilogy” ( Amores Perros, 21 grams, Babel) . He narrates multiple stores pivoting around an existential moment in all three films. In these three films, he allowed individual to take the center stage and put them in situations which tests their morality, principles, decisions and ethics. Human frailty, resilience, and validation were fundamental themes explored in these films. Now let’s scrutinize each of his films with much more clarity.

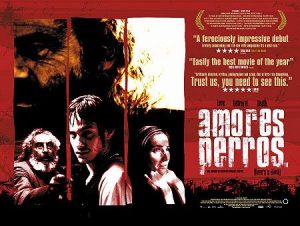

Amores perros (2000)

Amores perros is rooted in class and conflict. All three stories revolves around the mean Mexico streets, where there is no escapism. You either accept the life or accept the consequences when you alter it. Two rebellious brother destroy the fabric of their family and themselves in their fight over lust and money. One of the brother earns money by fighting his dog and plans to escape with his brother’s pregnant wife. A middle class publisher, leaves his mundane life and moves in with a highly successful model. This narcisstic model loses her leg in an accident with the one of the brother. Dilemma conjures in the minds of the publisher whether to take care of the model, who is more in love with her dog or revert back to his normal life with his loving wife and children. In the third story, he focuses on an intellectual hit man, a former professor and anti- government Marxist guerilla revolutionary turned murder, who lives the life of an outcast in Mexico with the street dogs. He left all the comfort of his life for the revolution. And the only purpose of his life is to gain in touch with his estranged daughter. When everybody is busy carving out their happiness model, the unpredictability of the modern existential world can turn the whole story upside down. This uncertainty is what intrigues Inarritu in Amores perros.

Amores perros is rooted in class and conflict. All three stories revolves around the mean Mexico streets, where there is no escapism. You either accept the life or accept the consequences when you alter it. Two rebellious brother destroy the fabric of their family and themselves in their fight over lust and money. One of the brother earns money by fighting his dog and plans to escape with his brother’s pregnant wife. A middle class publisher, leaves his mundane life and moves in with a highly successful model. This narcisstic model loses her leg in an accident with the one of the brother. Dilemma conjures in the minds of the publisher whether to take care of the model, who is more in love with her dog or revert back to his normal life with his loving wife and children. In the third story, he focuses on an intellectual hit man, a former professor and anti- government Marxist guerilla revolutionary turned murder, who lives the life of an outcast in Mexico with the street dogs. He left all the comfort of his life for the revolution. And the only purpose of his life is to gain in touch with his estranged daughter. When everybody is busy carving out their happiness model, the unpredictability of the modern existential world can turn the whole story upside down. This uncertainty is what intrigues Inarritu in Amores perros.

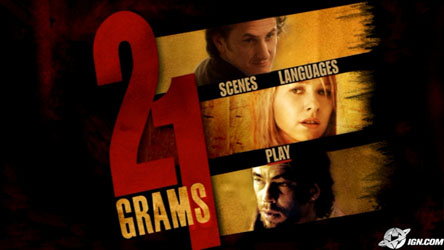

21 grams (2003)

Inarritu deepens the exploration of class structures, focuses on religion as a source of misbelief and alienation and offers a social critique of the world in the film. A middle class once jailed man (Del Toro) struggles to find deeper meaning of his wretched life through evangelicalism only to discover that it is he who actually navigates and commands his life. Meanwhile, an ailing math professor (Penn) needs a heart transplant to survive. He gets a new heart, and his endeavor to find the owner of the heart gives him new love in the process. A middle class wife (Watts) finds happiness and redemption from her drug ridden life, in her comfortable middle-class husband and children, but unfortunately she loses them in a random hit and run accident. She finds new love with the math professor and then gains a second chance at redemption when she discovers she’s pregnant to yet another dead man. It is the clash of such antagonisms and conflicts that drives 21 Grams. Watts’s obsessive need for vengeance, Del Toro’s compulsion for absolving self-sacrifice, results in the death of the relatively innocent math professor (Penn). Innaritu makes innocent dies in 21 grams, as if the only crime they committed were aligning with flawed people. The three powerful stories assimilate into a single narrative, like a puzzle, which the viewer completely conjoins by the end of the film.

Inarritu deepens the exploration of class structures, focuses on religion as a source of misbelief and alienation and offers a social critique of the world in the film. A middle class once jailed man (Del Toro) struggles to find deeper meaning of his wretched life through evangelicalism only to discover that it is he who actually navigates and commands his life. Meanwhile, an ailing math professor (Penn) needs a heart transplant to survive. He gets a new heart, and his endeavor to find the owner of the heart gives him new love in the process. A middle class wife (Watts) finds happiness and redemption from her drug ridden life, in her comfortable middle-class husband and children, but unfortunately she loses them in a random hit and run accident. She finds new love with the math professor and then gains a second chance at redemption when she discovers she’s pregnant to yet another dead man. It is the clash of such antagonisms and conflicts that drives 21 Grams. Watts’s obsessive need for vengeance, Del Toro’s compulsion for absolving self-sacrifice, results in the death of the relatively innocent math professor (Penn). Innaritu makes innocent dies in 21 grams, as if the only crime they committed were aligning with flawed people. The three powerful stories assimilate into a single narrative, like a puzzle, which the viewer completely conjoins by the end of the film.

Babel (2006)

Babel explores the same underlying themes like relationships between parents, children, siblings, sexual frustration and death. Inarritu brings in another aspect in babel, the role of government and its relation with people of various socio economic strata. The power equation and behavior of police varies across Japan, Morocco, USA and Mexico. But their attitude towards people belonging to lower socio economic levels remains universal. Babel tells the story of a hunting guide who is given a rifle for his services. He exchanges this rifle with his neighbor for some money and goat. The neighbor’s son carelessly shoot the rifle at a tourist bus. An American woman is injured in the process, which spurs an international “terrorist” incident. The American woman’s kids are in the USA, looked after by their Nanny, who is desperate to attend her son’s wedding. Meanwhile, a Japanese girls struggles with her sexual frustration. These four stories across the world are interwoven into a compelling narrative by reordering structure, context and time frames. It explores that even an irresponsible action by a naïve child can trigger an event which can have a global impact. “World is a small place to live in”, babel clearly encompasses this message.

Babel explores the same underlying themes like relationships between parents, children, siblings, sexual frustration and death. Inarritu brings in another aspect in babel, the role of government and its relation with people of various socio economic strata. The power equation and behavior of police varies across Japan, Morocco, USA and Mexico. But their attitude towards people belonging to lower socio economic levels remains universal. Babel tells the story of a hunting guide who is given a rifle for his services. He exchanges this rifle with his neighbor for some money and goat. The neighbor’s son carelessly shoot the rifle at a tourist bus. An American woman is injured in the process, which spurs an international “terrorist” incident. The American woman’s kids are in the USA, looked after by their Nanny, who is desperate to attend her son’s wedding. Meanwhile, a Japanese girls struggles with her sexual frustration. These four stories across the world are interwoven into a compelling narrative by reordering structure, context and time frames. It explores that even an irresponsible action by a naïve child can trigger an event which can have a global impact. “World is a small place to live in”, babel clearly encompasses this message.