I watched Breakfast Club when I was in 10th grade. Even though the film was set in America and American culture, there was something about five kids coming together in detention, who always felt misunderstood, that really resonated with me. And I admit, in the last scene of the film, when Brian (Anthony Michael Hall) signs off with “Sincerely yours, The Breakfast Club,” cutting to the final shot of Bender’s iconic fist pump, I was exhilarated. Recently when I rewatched the film, I was squirming. I couldn’t believe how much Bender sexually harassed Claire (Molly Ringwald) throughout the film and still got the girl at the end.

Obviously, it’s not only Breakfast Club but all the other teen films that Hughes wrote – starting with Sixteen Candles (1984), moving on to The Breakfast Club, Weird Science (both 1985), Pretty in Pink, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off (both 1986) and Some Kind of Wonderful (1987).

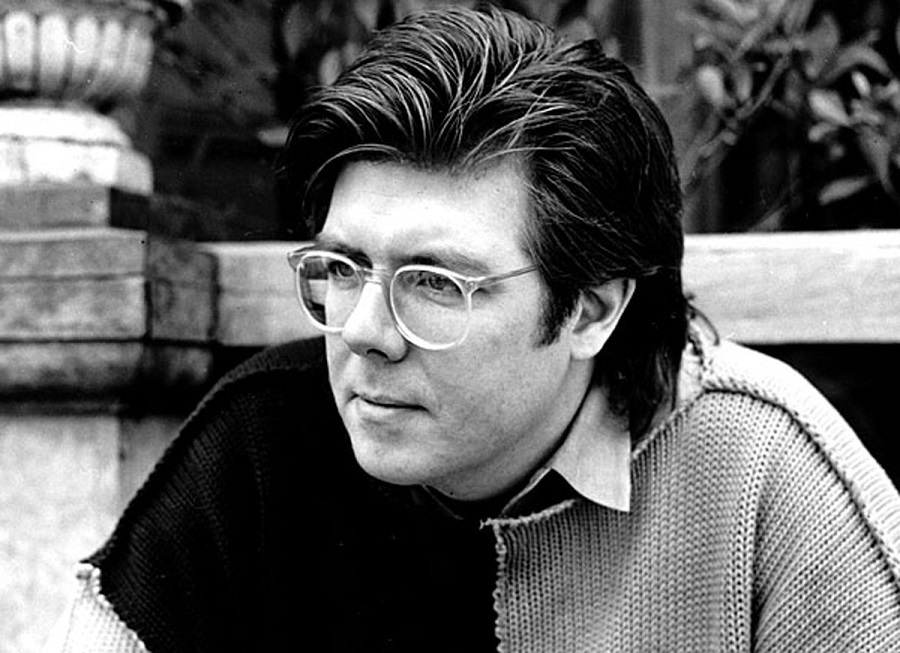

John Hughes is known to have redefined what it meant to be a teenager for the American culture. In the world of 1980s cinema, Hughes was going to create ripples with his influential coming-of-age genres which will forever influence pop culture. It was largely because of his subject matter. No one had taken young people seriously enough to find and tell real stories about them. They were, in a way, invisibilized from the cinema as they were from society. Hughes, in contrast to the teen sex comedies that were coming out (Porky’s and Fast Times at Ridgemont High), portrayed teens as humans with dreams, fear, and a life of their own. His cinema was empathetic and sensitive towards them, capturing the realities of growing up and teenage angst.

The struggles of the youth are real and what happens in high school is the microcosm of what happens in the real world – bullying, classism, harassment, sexual and identity politics, nepotism, passion, love, etc. The plot may seem trivial at first though. For example, the central storyline of Pretty in Pink involves a girl being invited and then uninvited to prom. Or how in Sixteen Candles, her family and crush forgets her birthday. And in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, both Ferris hates rules and how he and his sister are competing for their parent’s attention. Seemingly flimsy, it actually explores the deep insecurities of a teenager, mostly female teenagers – peer pressure, classist mates, beauty myths, gender roles, non-loving parents, bullying, etc. I, myself an insecure teen once, deeply related to such emotions.

Navigating high school is very difficult because there is always a conflict between finding who you are and who you are supposed to be; between wanting to do too much and often feeling helpless. It is hard to tread the halls of schools than one may realize. I have largely been unpopular in my school days, gazing longingly at the most popular group, and hoping to be a part of them.

I have been insecure and desperate to look like the pretty girls and wanted male attention more than anything. I have formed my worldview and its principles in high school, some of them which I shed and some which I still carry. The psychological paths I went down are directly and indirectly a result of my experiences in high school and also as a teenager.

Some Kind of Wonderful was an interesting watch because no one got the beautiful girl in the end. The guy (Kieth) who was pursuing the beautiful girl (Amanda) realized he loves his best friend, the unpopular tom-boy (Watts) instead. This movie also has several high school tropes – the beautiful girl, the asshole rich boyfriend, the artsy, outcaste guy, the tom-boy best friend, etc.

However, I loved how in the end, Amanda slaps her rich ex-boyfriend and realizes she doesn’t need to be treated in a worthless manner. However this, like all Hughes films, has a conservative ending – a white, pure virgin girl getting the rich, handsome guy. SKOW saw two outcasts coming together, which was amazing, but it still lacked considerable diversity.

There are several problematic politics of Hughes films and in the age of #MeToo, one wonders where they stand. Sixteen Candles has a very troublesome scene of non-consensual sex. This and other scenes where girls are just a conquest that the male has to win over. I could go on and on of severe controversial scenes of these 6 teen films. As I mentioned, when I rewatched The Breakfast Club, I was annoyed and uncomfortable with the character of Bender. However, my heart was warmed during several moments of the film as well, such as when they sit down to discuss their life problems or when they run down the halls escaping the teacher.

It left me wondering: Is it possible to both love and oppose the art you admire? Is it possible for me to oppose the politics of The Breakfast Club and still love it for what it was trying to say? We live in a world that aims to drive away any form of nuance, insisting we look at things in black and white. By that logic, John Hughes was either a masterful genius or a predator misogynistic. With the conversations around gender and feminism increasing, John Hughes can easily be seen as the latter.

But how can one forget that most of his teen films were focused on teen girls and their hopes and desires? Or how can one overlook the classic line in The Breakfast Club calling out the Madonna-whore complex in the society that is obsessed with female virginity:

“Well, if you say you haven’t, you’re a prude. If you say you have you’re a slut. It’s a trap. You want to but you can’t, and when you do you wish you didn’t, right?”

And isn’t that the best kind of cinema anyways? That engages and confuses you rather than blocking any sort of conversation?

What I am suggesting is that maybe one can admire and love what Hughes was doing while still commenting on the problematics of it. Maybe one can find ways to talk about art and activism where both are in a form of engagement and conversation. Young people, at the end of the day, want to be seen and understood. They want to be treated with the dignity and respect they deserve as humans. Most teenagers carry on the burden of their roles because they don’t know any better. It is because it is better to be with identity than to be nothing. It is better to remain within the status quo than break it. Sometimes, the most popular girl is actually a lesbian or the most unpopular guy actually likes going to parties.

In school, we learn the status quo and how easy it is to hide behind some fictionalized version of oneself than to ever be two different things at the same time. As adults, we get better at it. But as young people, it is both painful and heartbreaking. Hence, at times like these, one really wants someone to hold their hand and tell them it will get better. I certainly did. And when no one was around, cinema was. Whenever I am perplexed about the questions I posed above, I remember that 10th grade insecure and scared girl, who watched The Breakfast Club and felt less alone. She felt like her problems and fears were valid and learned that there was no one way to be cool. And how even the cool people feel uncool most of the time.