“You are so pretty, you could have been a girl”, a sultry Kalki, aka Mimi, gleaming in her anglicized fair complexion, shot at a timid, rabbit-eyed Vikrant, aka Shutu. Just one of those passing, almost mild even, instances the latter had been subjected to the bullying scrutiny of the hovering eyes.

Vikrant goes on enveloping us with his coy, sidelong, submissive glances, perennially with a glint of fear that speaks louder than most of his mouthed words that raise only a little above a firm whisper.

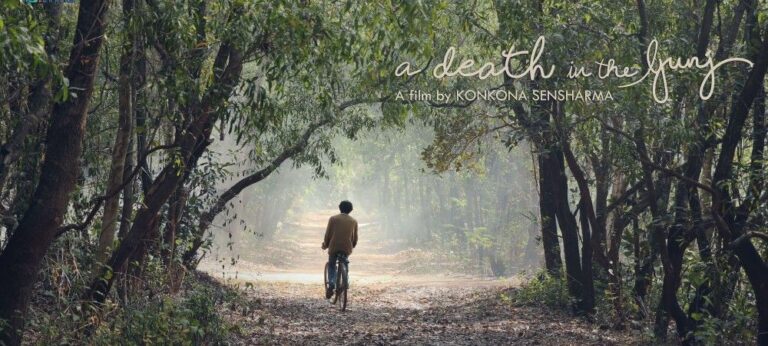

Konkona Sen Sharma’s directorial debut, Death in the Gunj, takes us on a time tour to the dusty, dingy lanes of a rural town, McCluskiegunj, in the 70s, an era rampant of fancy sideburns and bell-bottomed high waisted denims.

We are introduced to a group of young people vacationing their way into the town, in a sprawling house that once used to be a resort for the Anglo people, now taken in by Ashok (Om Puri) and Anupama Sharma (Tanuja). It’s difficult to shrug off the post-colonial hangover the frame reeks of. There’s Nandu(Gulshan Devaiya) the mildly belligerent son of the Sharma, his attractive, kind wife Bonnie (Tillotoma Shome), a precocious eight year old, Tani, Mimi, the vulnerable seductress dealing with her personal conflicts over men, Shutu, grieving over a recently lost parent, and two other garrulous bully friends of Nandu, Vikram and Brian (Ranvir Shorey and Jim Sarbh respectively). What follows is a series of young people whisking away evenings dancing and drinking and baring themselves down with inebriated decisions, seeking dead people, silly fights, flirtations bordering on the line of adultery, all decking up like cards to lead up to a penultimate death that we have been accounted in the very first scene of the film. The slow paced life and air of the remote town carves out a conducive atmosphere for the young people to indulge in follies and pesky pranks. There’s an ease and a sense of intoxication that lulls you into their conviviality.

What follows is a series of young people whisking away evenings dancing and drinking and baring themselves down with inebriated decisions, seeking dead people, silly fights, flirtations bordering on the line of adultery, all decking up like cards to lead up to a penultimate death that we have been accounted in the very first scene of the film. The slow paced life and air of the remote town carves out a conducive atmosphere for the young people to indulge in follies and pesky pranks. There’s an ease and a sense of intoxication that lulls you into their conviviality.

More often than not, when I try to determine the movie’s genre, I am left baffled at how much it is layered with to shake itself out of a definite label. Primarily it seems like a successful attempt at decoding the various complexities and struggles of relationships, but it goes on to be much more than that. It takes on an empathetic stance when we see Shutu being bullied and cowered down endlessly by the alpha males. There is also an underlying theme of alienation and estrangement yet again breathed out by him effortlessly as he seeks solace in the company of an eight year old who is unaffected by his real self, over the judging eyes of the adults, which constantly seem to be scrutinizing and mocking his vulnerabilities.

Much of the unlayering of emotions is a big shoutout to Konkona’s deep understanding of the human mind that puts out for a treaty bite in certain poignant scenes. One of them being when Shutu ensconces himself in his father’s sweater and cries himself to sleep.

Konkona takes her own sweet little time to help us get along with each of the characters and their defining traits. Nandu is a dominating male presence with a decisive gait, Bonnie is a doting wife and a mother who is also the only one in the parade to sympathise if not empathize with Shutu, Mimi is often looked at with a scorn by the imperious Anupama for the former’s promiscuity or rather her racial origin, Vikram is the loud bully engaging in courting flirtations with his past. Vikrant shines on in his performance, that in itself says a lot about him as an actor, given he is planted in an assemblage of other actors of great nuance and expertise. He stands underwhelmingly strong to try and seek out validation for his masculinity that is shadowed beneath his boyish features and overtly sensitive nature.

Vikrant shines on in his performance, that in itself says a lot about him as an actor, given he is planted in an assemblage of other actors of great nuance and expertise. He stands underwhelmingly strong to try and seek out validation for his masculinity that is shadowed beneath his boyish features and overtly sensitive nature.

There’s no performance that feels out of tune to hinder the pace of the film. The mood of the frame is maintained equitably throughout through its mellowed yellow and brown reel, which at times struggles keeping up with the contextual dialogues that almost seem to be a little too contemporary for an era set some 5 decades ago. Inclusion of tribal song and dance sequences add up to the local flavor that would linger on for a while even after you are done with the film. Konkona steers clear out of the cliches and stereotypes to serve us a tamed, refined yet a raw piece of art that promises better times in our Bollywood. That’s the cinema I’d definitely buy tickets for.